Study design

This quasi-experimental study assessed the impact of an intervention—comprising personalized oral health education, provision of a basic oral hygiene kit, and behavior modification through a questionnaire based on HAPA and MI constructs—on oral hygiene practices among residents of informal settlement in Bhubaneswar. The study evaluated changes in oral hygiene behaviors and clinical oral health outcomes, such as plaque index and OHI-S, before and after the intervention.

Type of study

This study primarily involved quantitative data collection and analysis. Pre- and post-intervention data on participants’ behavior and oral health outcomes were collected to determine the intervention’s effectiveness on oral hygiene practices.

Study site

We conducted oral health screening camps among the residents of informal settlements at three wards of Bhubaneswar, such as ward number 30, 46 and 55. These individuals belong to low-income groups with no or unstable employments such as daily wage labors, street vendors, domestic workers, construction workers etc. Their literacy level is poor. Sanitation and ventilation in those settlements are poor. They have limited access to health care including oral health care, relying mostly on quacks, self-medication or alternative medicine rather than professional dental care. Most importantly nutritional deficiency and lack of autonomy in health relation decisions are prevalent in these settlements.

Duration of study

This study was conducted over two months, from October 24, 2023, to December 24, 2023, following approval from the Institutional Ethics Committee (Approval No.: EC/NEW/INST/2022/3235).

Number of subjects

A total of 110 adult participants, aged 18–60, were initially screened. Based on inclusion and exclusion criteria, 45 participants were selected for the study. Post hoc power analysis using G*Power (version 3.1.9.7) revealed a study power of 98% with an effect size of 0.5, a significance level of 0.05, and a sample size of 45 participants. Prior to participation, all eligible individuals were provided with a detailed explanation of the study objectives, procedures, potential benefits, and risks in their native language. Participants were informed that their participation was voluntary and that they could withdraw at any stage without any consequences. Written informed consent was obtained from each participant before enrollment, and for those with limited literacy, verbal consent was recorded in the presence of a witness. To ensure confidentiality, all data collected were anonymized and coded, with no personally identifiable information linked to the research findings. Data were stored securely and were accessible only to the investigators (SP and PR).

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Participants eligible for inclusion in the study were adults aged 18–60 years diagnosed with gingivitis, who were willing to meet all study requirements, possessed the cognitive ability to understand and follow oral hygiene instructions, and had at least 12 teeth, including at least one index tooth to evaluate plaque and OHI-S.

Exclusion criteria included individuals who were current smokers or had quit smoking within the past year, those who were pregnant, or those with systemic diseases that could impact study outcomes, such as diabetes, hypertension, neurological or psychiatric disorders, systemic infections, cancer, or HIV/AIDS. Participants were also excluded if they were on long-term antibiotic therapy, undergoing orthodontic treatment, or diagnosed with periodontitis.

Sampling method

Convenience or purposive sampling was followed by collaborating with local health clinics, community centers, or NGOs to identify potential residents of informal settlements who gave their consent to participate.

Data collection

T0 (baseline): After obtaining informed consent, the baseline oral health status and oral hygiene behavior of all participants (n = 45) were assessed by one intern and one faculty member. Data on demographic details (name, age, gender, systemic history, habits), OHI-S [20], and plaque index [21] were recorded. Baseline oral hygiene behavior was assessed using a validated questionnaire based on MI and HAPA constructs. The questionnaire was developed based on established Motivational Interviewing (MI) and Health Action Process Approach (HAPA) frameworks, ensuring theoretical validity. A thorough literature review guided the selection of items relevant to oral hygiene behavior. To establish content validity, a panel of experts in oral health behavior, public health, and behavioral psychology reviewed the questionnaire for clarity, relevance, and completeness, refining it accordingly. It was then pilot-tested on a small sample from the target population to assess comprehensibility and response patterns, with necessary modifications made based on participant feedback. The questionnaire measured four behavioral constructs which included outcome expectancies (OE), self-efficacy (SE), intention (I), and perceived barriers (PB) using items adapted from Schwarzer et al. [6] and Gillam et al. [22]. The constructs consisted of five OE items, six SE items, four I items, and three PB items, each scored on a five-point Likert scale (1 = strongly disagree to 5 = strongly agree). Personalized as well as community based oral health education was provided, and oral hygiene kits were distributed.

Interventions

Behavior modification intervention

Each selected participant completed a custom-designed questionnaire (Supplementary Table 1) and responses were recorded in the data extraction sheet. The responses to the questionnaires were collected anonymously without linking responses to individual participants. No identifying information was recorded, ensuring complete anonymity in data collection and analysis.

Personalized oral health education

Education was delivered at both community and individual levels. Community-level workshops included motivational talks on oral hygiene’s benefits, proper brushing techniques, oral health’s role in systemic health, lifestyle modifications, and dietary influences on oral health The lectures were delivered by faculties and post graduate dental students of community dentistry department outside those settlements addressing small groups of 15 people in three sessions. Audiovisual aids through power point presentation were used to demonstrate the brushing and flossing techniques. At the individual level, one-on-one sessions were tailored to each participant’s specific needs, covering brushing, flossing, and mouthwash use. One on one session was also taken by the faculties and post graduate dental students of community dentistry department.

Distribution of oral care kit

Each participant received an oral hygiene kit, including a toothbrush, toothpaste, and dental floss.

T1 (Follow up results): After one month, participants were re-evaluated to assess changes in plaque index, OHI-S, and behavioral constructs using the same custom-designed questionnaire from the baseline.

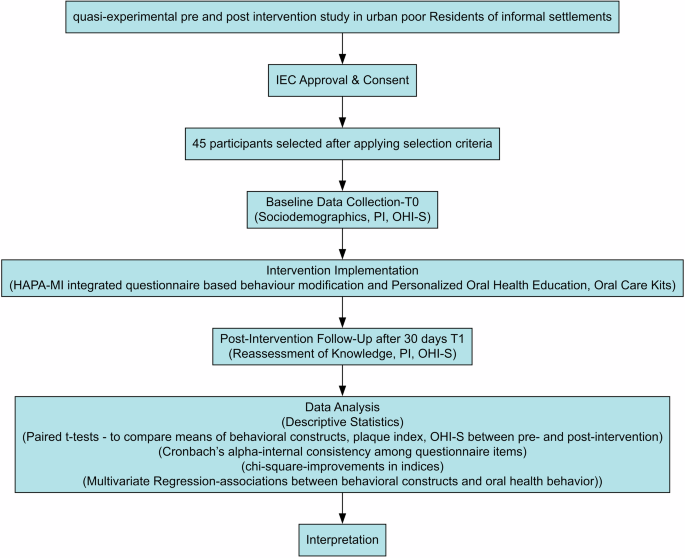

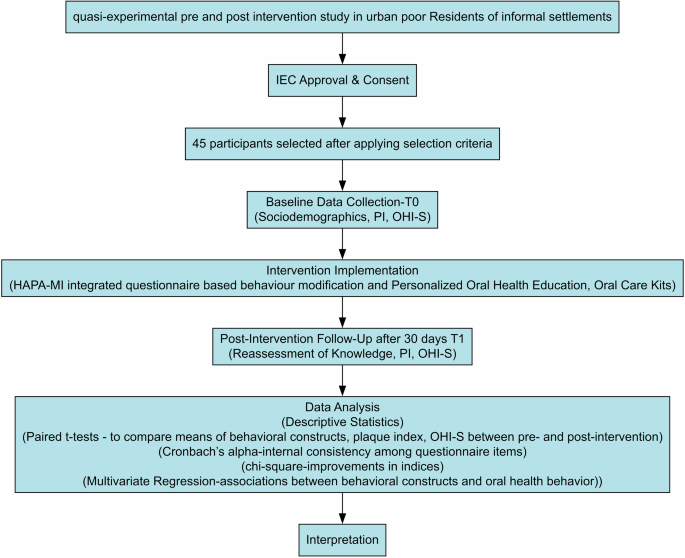

We have depicted the methodology schematically in Fig. 1.

Schematic description of the methodology.

Statistical analysis

Data analysis was conducted using SPSS for Mac (version 28, IBM Corporation, Armonk, NY, USA). A p-value ≤ 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Categorical variables, such as age, gender, and habits, are presented as frequencies and percentages. Continuous variables, including plaque index, OHI-S, and questionnaire items, are presented as means. The baseline oral health behavior of residents of informal settlements was assessed by summarizing Likert scale responses for each item in the constructs. Paired t-tests compared the means of behavioral constructs, plaque index, and OHI-S between pre- and post-intervention groups. Cronbach’s alpha measured the internal consistency among questionnaire items, while chi-square tests examined improvements in index grades and associations between behavioral constructs and oral health behavior at T0 and T1. Post-intervention, each behavioral construct was assessed in three categories. If the post-intervention score is more than pre-intervention score, then improvement exists. If both scores are equal or post intervention score is less than pre-intervention score, then no improvement exist. The differences in post and pre-intervention score of PI and OHI-S were calculated. To evaluate the influence of change in behavioral constructs on differences in plaque index and OHI-S we conducted multivariate regression analysis.

link